NormandyOn segmentation, and “cool” photography

Dear friends,

Two years ago, at a photobook fair, a gallery owner walked up to my booth and asked: “Heb je vette fotografie?” / “Do you have cool photography?”

I had no idea what she meant. To be honest—I still don’t.

Since then, the question has lingered. What is cool photography, anyway? I can only guess. Judging by the kind of work she shows in her gallery, I suspect she meant photography without any fuss. No collages, no mixed media, no playful experiments. Just pure, straight-up photography. Whatever that means.

Ever since I started working with photography, I’ve felt the need to divide things up a bit—some kind of segmentation. As far as I know, there’s no clear map of the field.

And I’d love one. I want to understand which parts I’m moving through, so I can get a better grip on my own work—and reflect on it with a little more precision.

There are movements (historical or ideological), styles (aesthetic), and market segments (fashion, documentary, fine art, commercial photography). And they’re constantly bleeding into one another. On top of that, it feels like anything goes these days—as long as it’s…

Well—as long as it’s what, exactly? Part of the zeitgeist? Tackling social issues? Liked by the cultural elite? Pretty enough to hang above the couch? Refreshingly different? Easy to sell?

I have no clue. But I’m going to find out.

A quick heads-up though: the literature I’ve been consulting is… let’s say, not exactly crystal clear. The first book I grabbed (The Photobook, Volume II by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger) hits you with a tidal wave of information. Don’t get me wrong—it’s brilliant, and easily my favourite photobook. But it also feels like getting caught in a downpour of references, names, movements and quotes. So I’m trying to find a thread to follow.

One early structure I’ve latched onto is Mirrors and Windows, a MoMA exhibition from 1978, curated by John Szarkowski.

According to this concept, there are two types of photographers: “the mirror type,” who uses the camera to talk about themselves, and “the window type,” who points it at the world instead. Szarkowski preferred the latter. And thanks in part to his influence, the objective approach became a driving force in American photography at the time.

Inside that category, a bunch of styles emerged—you could say subsegments, this time based on form and aesthetic. Expressive documentary still relied on the large-format camera. But when the small 35mm camera became widespread, the style loosened up. That paved the way for things like stream-of-consciousness photography (diaristic and spontaneous) and personal or snapshot photography. Then there was straight photography (no author, no art) and conceptual photography. I’m especially drawn to the latter—because, as you know, I’ve always loved sequences and ideas that unfold across pages. But lately, I’ve been challenging myself to work with just a single image. So for now, I’m letting conceptual photography rest quietly in the background.

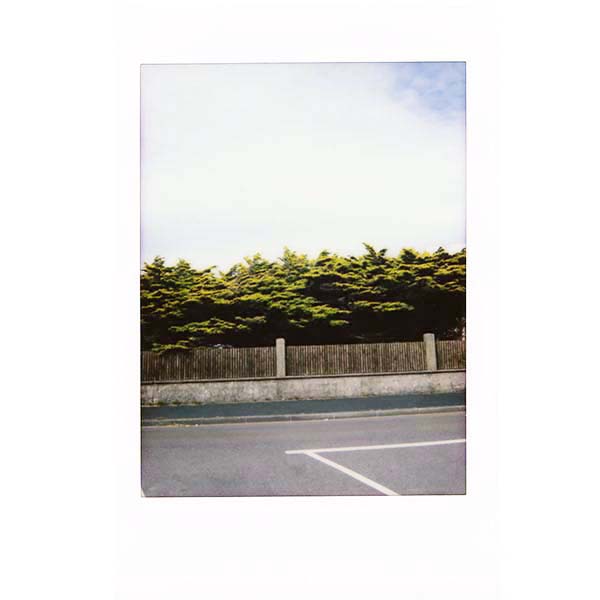

The photo at the top of this post was taken in France, during a holiday in Normandy, on the boulevard of my favourite seaside town. I’ve photographed the villas on the boulevard countless times over the years—but this one, of a simple green fence, stood out to me. It felt oddly complete.

And now, back to segmentation. My photo is a window photo, and I’d place it in the stream-of-consciousness corner. Whether it counts as cool photography? I honestly don’t know.

Best,

Mémé